San Blas, Sweet and Sour

/We first spied the telltale “tippy-tops” of the palm trees of the islands poking just barely above the horizon—our first hint that we were almost there—after about a week at sea. The San Blas Islands were every bit as much as one would imagine pristine white-sand, coral-reefed tropical islands to be: picture-perfect postcard atolls with crystal clear, aqua-blue water lagoons that lapped deserted, powder-sugared bleached beaches, with the requisite clump of coconut trees leaning just inside the photo frame. The only thing missing was the proverbial tattered shipwrecked cartoon character.

Off the Caribbean coast of Panama, the San Blas Islands fall somewhat under the radar of the more popular tourist destinations in that part of the world. Not terribly far from the coast, they are, nevertheless, somewhat isolated and it takes a little extra effort and some “doing” to get there for most tourists. Since we were already on a sailboat, and the San Blas Islands were situated along our route to Panama, we targeted this veritable tropical paradise as we sailed due west after a four-month stay in what was then called the Netherland Antilles of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao.

Home to the Cuna Indians (also “Kuna”), the San Blas Islands are an autonomous territory of Panama, and a unique example of how a people determined to safeguard their customs and distinctive lifestyle can succeed in spite of the menacing incursion of modern life. The Cunas have managed to deftly preserve their traditions, ceremonies, dress, and language while concurrently bowing to some concessions to the world around them, having integrated a limited amount of organized tourism to generate some revenue.

Our sail to these islands was calm and non-eventful, but an undercurrent of worry and mounting stress reigned onboard. Michel was not well and he was getting noticeably worse as he had a constant high fever and was losing weight. The atmosphere was tense and strained, yet we tried to ignore it for the time being and enjoy the San Blas Islands just the same.

With only 49 islands inhabited of the over 378 of the San Blas, there are many isolated, unpopulated idyllic anchorages of incredible beauty and peaceful solitude that just beckoned to be discovered. We cherished such times, because contrary to what many may think, such opportunities were actually few and far between with our lifestyle. They provided good occasions for meditating upon our condition and status; taking stock of where we had been, where we think we may go; and a good time to catch up on mundane chores, repairs, school work, and getting a leg up on the larder by baking an extra loaf of bread or two, or getting a head start on the next batch of yogurt. An unexpected good catch of the day during an afternoon dive with the boys sometimes rounded things out perfectly.

One such occasion of a "good catch" was a decent-sized stingray that Michel caught with the spear gun while snorkeling with the boys, 7 and 9 years old at the time. Locals had also warned of roaming sharks and indeed Michel, Sean, and Brendan breathlessly confirmed this after just such an encounter during an afternoon of snorkeling. Although only a brief, "swim-by," it was just enough to be too close for comfort. Brendan frantically scrambled onto Michel's back, clutching at his neck for safekeeping, while Sean busied himself noting the shark's markings and telltale signs of its particular breed. Upon surfacing, they all recounted excitedly what they had seen, and Sean was convinced he knew exactly what kind it was.

Along with our thirst to discover lands, landscapes, and sights in our travels, we were also strongly motivated by curiosity to delve into the cultures, customs, languages, and history of our host countries. After a first few days of serenity and regrouping in our paradise lagoon, we lifted anchor for one of the nearby, inhabited islands where we hoped to acquaint ourselves a bit with some locals. Not being well charted, the San Blas Islands required that we use "sight navigation" to get around. We only had just a few vague sketches handed down from past visiting boats, so either Michel or I positioned ourselves in a lookout perch at the bow of the boat. With this viewpoint and hand signals, the bow lookout could indicate the best path to the helmsman as to where to pass between rocks and coral reefs according to the change in color of the water. The water was so incredibly clear that white sandy channels or passageways were obvious. Anything else was doubtful and to be avoided. This system served us well, and onward we weaved through the islands.

Graciously welcomed by Cuna villagers at our first inhabited anchorage, we were bid to wander freely on land. They waved and smiled as we meandered through expanses of sandy grassy areas, shaded by coconut tree canopies and bordered by their simple, thatched-roof bamboo huts. Colorful laundry hung to dry and wispy smoke wafted up from their cook fires, most usually smoking fish. Although a few villages on some of the islands host simple rustic, yet charming, atypical tourist huts, and minimal facilities or efficiencies that mesh easily with their village livelihoods, we were still mindful that this island was not one of those and we took care to tread lightly, in an effort to respect their privacy and preserve such an opportunity for cruisers who may later follow in our footsteps.

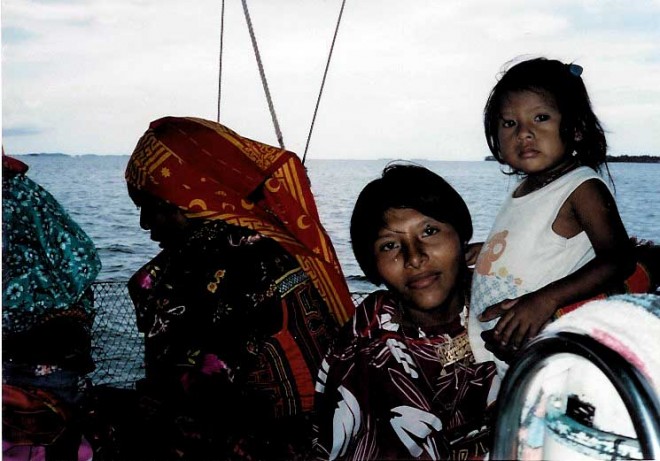

Perhaps the most famous and outstanding hallmarks of the Cuna Indians are the women’s handmade molas: intricate, exquisite, and uniquely colorful hand-sewn blouses as well as 12-inch square swatches of multi-layered cloth, embroidered in reverse appliqué of intricate designs and patterns that evoke their culture and surroundings. This is an exclusive activity of the Cuna women and they actively lead the business of selling and trading these handcrafted items. Although reserved and often shy, the women were nonetheless anxious to trade or sell their molas. Several of them would come alongside our boat, escorted in a hand-hewn dugout or “cayuca” by some of the village men who usually spoke Spanish, serving as interpreters. In general, the women only spoke their Cuna language.

Although they were pleased to accept cash payments for molas, they were also just as pleased, if not more so, to engage in trading or bartering for household items. A particular hit was small children’s clothing, and I became quite a popular source as I doled out several of Brendan’s earlier baby things in exchange for molas that caught my fancy. This all took place amidst a calm, pleasant, and non-aggressive atmosphere. No hard sell here. Often they would just paddle by for a brief visit in the evenings, offering fruit, fish or lobsters, or seek a bit of conversation, indulging their curiosity about us.

We were always struck by how stylish the women were in their colorful mola blouses, wrap-around pareo or sarong skirts, handmade beaded bracelets and anklets, their deep-black hair fashioned in spartan bobbed cuts, often topped with bright red bandana headdresses, and bedecked with multiple earrings and nose rings. Their outfits were always bright, loud colors with terribly mismatched flowers, plaids and whatever swatches of fabric they got hold of, but somehow it all came together and they cut quite striking figures. I could never understand how they could be so dressed to the nines in such heat!

After several days we lifted anchor for the main island, Rio Sidra. What a difference from the calm, serene lagoons we knew up to that point. Rio Sidra was an explosion of population! In direct contrast to the previous sparsely inhabited islands we had visited, I don't think there was but two feet separating each thatched roof hut from another, all lined up snuggly along labyrinths of narrow, beaten-dirt paths that criss-crossed the island. There were no lonely coconut trees, no secluded white sandy beaches or grassy expanses. All one could see was wall-to-wall, wood-plank or bamboo stick huts—home to about 2000 people—we were told. For all this humanity crammed together, it was amazingly clean. No trash or rotten food lingered, and no unpleasant odors.

Our welcome to Rio Sidra was equally surprising. Reprising a scene from some old movie where grizzled sailors arrive on a 1700-1800s-era square rigger in a picturesque South Pacific lagoon, welcomed by the entire island population in outrigger canoes launching en masse from the beach, we were likewise hailed by an armada of "cayucas"—a veritable assault—of shouting, smiling people. They rowed and crowded alongside us as we anchored, hanging on to sides of our boat, waved their molas, and bid us to come ashore. There were several other sailboats already at anchor, and as others arrived a few days after us, and the same scene unfolded, we learned that this was the norm.

Children were like ants; they were active and everywhere. They immediately swept up Sean and Brendan, gobbling them up in soccer games. A few of them also had an old leaky dugout, and they would entice our boys to swim and play with them for hours, climbing in and out of the old sinking hollowed-out tree trunk, having a grand old time.

On land we met Daniel, a resident, who showed us around and invited us into his hut to meet his family. He also invited us to a traditional ceremonial event set to unfold in the coming days, marking the passage of an adolescent girl into womanhood. On this particular occasion, the ceremony was for two girls. Intrigued and honored by this invitation, we eagerly accepted.

A few days later, we were escorted into in a large central, open-air thatched-roof meeting area of sorts, reserved for tribal ceremonies and the like. It was a colorful, yet solemn scene, with the women forming a bright tapestry of mola blouses and sarongs all seated along one side of the "room" as they smoked pipes. The men sat facing them on the opposite side. An inner circle of "wise men" or priests of sorts, clad in rose-colored shirts, ties, hats, and smoking large crude cigars, were seated around pots of burning cacao incense. Every few minutes these select men would stand and circulate around the room, blowing smoke in the observers' faces to "purify the souls."

Many casks of "chicha," a fermented sugarcane/corn drink concoction, were also widely consumed over the next several days, while a consistent hum of ceremonial incantations—rather reminiscent of Native American chanting—droned on under the "tent" for the duration. Finally, in preparation for the culmination of these festivities, the two adolescent girls were prepared for their "passage." Two 3 ft. deep holes were specially dug for the girls where they dutifully spent several hours as part of their preparation process. Then, in what seemed to symbolize their new start, their heads were shaved and covered with a shawl. Before this was done, however, we were honored to have been escorted to view the girls in the special hut, since this was clearly a sacred ceremony.

Although "shamans," had their rightful place in Cuna society, the Cunas also seemed to recognize that modern medicine had a useful role as well. So it was that several of the village men came urgently knocking on our hull one evening: the village chief was not well and the nearest doctor could only be reached by boat and on foot, a two-day trek. It seems he hadn't been able to urinate for several days and consequently was in pain and terribly bloated. Most yachties possessed rather elaborate pharmacies onboard, and between us and a fellow yachtie anchored nearby, we gathered quite a stash of diuretic medication along with a catheter. Michel and the fellow sailor quickly embarked with the villagers to shore, and were escorted to the beach where the chief was laying on something of a table-like cot, elevated on a platform. Surrounded by men of the village holding a halo of brightly lit lanterns, "doctors" Michel and associate proceeded to ply the chief with copious amounts of diuretics, hoping to avoid a direct intervention with the catheter. The medication had an almost instantaneous effect, and the two yachties were practically anointed new savior shamans right then and there!

Before coming to Rio Sidra, we had met Arnulfo Robinson, a Cuna on Holandesa Cay, who also had a home on Rio Sidra. He found us again while we were at Rio Sidra and insisted we take a trip with him and his son upriver from the coastal mainland to visit a tribal cemetery. With his son, Arnulfo Jr., at the helm of a powerful outboard, Sean, Brendan, Michel, and I, along with another yachtie couple, all piled into a family-sized "cayuca." After quickly motoring to the shore, we seemed to punch a hole in the shore vegetation and were suddenly cruising down a very picturesque and peaceful jungle river. At one point we passed another cayuca and they engaged our chauffeur in a brief conversation. Arnulfo Jr. suddenly cut the engine. In his enthusiasm as a guide, it seems he had forgotten to respect the Cuna custom that the spirits of the deceased send “roots” downriver from their resting place in the cemetery nearby. Normally in such a case, outboard engines are forbidden.

Before long we tied up alongside the riverbank, and took a short walk into the forest to the cemetery—an obviously sacred spot for these people. There were many mounds of varying sizes (and noticeably those for children) in a clearing, yet easily hidden amid the jungle foliage. Several pots of burning incense graced the head of several graves. Several women were there tending to the sites as well. We were honored and struck by all this openness and genuine welcome extended to us by the Cunas. They seemed eager for us to learn about them, as if they understood that by spreading this knowledge among passersby would be a plus to keeping their civilization intact.

Our month of a San Blas experience was sweet and sublime, but suddenly it all turned so sour, tingeing my memories of San Blas as somewhat bittersweet. Michel was ill and we had been ignoring it. By the end of the month, he had deteriorated greatly, with a high fever, weight loss, weakened, exhausted, in pain, and finally a worrisome cough. He hadn't really enjoyed the San Blas as he could have. It was obvious that we had played with fire and lost, since by now it was the end of October, and following Michel's operation back in July to change his defibrillator battery, we were remiss in giving his post-operatory condition the proper care and attention needed. He returned to the boat in Curaçao from his operation in France while still in stiches and sporting a major post-operation dressing. We were to learn shortly that what could have been dealt with as a minor infection nipped in the bud, had developed into an advanced stage of septicemia. Enough. We must weigh anchor and head to Panama—very quickly! The American invasion of Panama in 1989 was imminent and by the time we sailed into Colon, it was indeed, a full panic in Panama (see vignette Panic in Panama, posted February 14, 2013).