Casablanca and Moroccan Charm

/It was another first for us. We landed in Africa—a new continent. Granted, we had made a brief, one-night stop in the Spanish enclave of Ceuta on the North African coast a few days earlier, but for all intents and purposes that was still Spain. This was Casablanca, Morocco, something completely different, and a door to the new and unknown.

Not knowing what to expect, many of my night-watch hours at sea were spent imagining and anticipating what might await us, all framed within the indelible and inescapable images engraved in my brain from the film “Casablanca.” We weren’t disappointed. It was a collision of two worlds: the old-world Medina with its narrow dirty, gritty streets and glittery maze of souks or marketplace stalls, peppered with veiled women in elegant robes, all encased within a bustling European city of cafes, boutiques, and traffic-buzzing boulevards. We were definitely out of our comfort zone, but we relished it. There were new images, new sounds, new smells. The harbor was filthy and polluted. Tar and fuel-covered wharfs and docks were part of a mosaic of decrepit buildings, a few half-sunken vessels, well-worn fishing boats, a hodge-podge of ragged stray cats and dogs, and a small posse of fishermen whiling away the time. It was creepy, eerie, and somewhat void of life, yet distinct with telltale signs of a Casablanca from the past.

Having arrived early afternoon, much of the rest of the day was spent hunting down the proper office and authorities to fulfill the entry formalities. Although fairly routine, it did turn out to be rather tedious, made even more unpleasant by a customs’ officer insistence we offer him a bottle of whiskey once he spied our case of “barter” stash purchased in Gibraltar. The word out on the cruising circuit was that this was a very useful currency in Brazil for an exchange of services. This officer was quite blatant with his request and Michel respectfully disagreed, refusing to surrender a bottle. Although the officer insisted, he eventually backed down, leaving us to wonder what sort of curse we might have incurred for later.

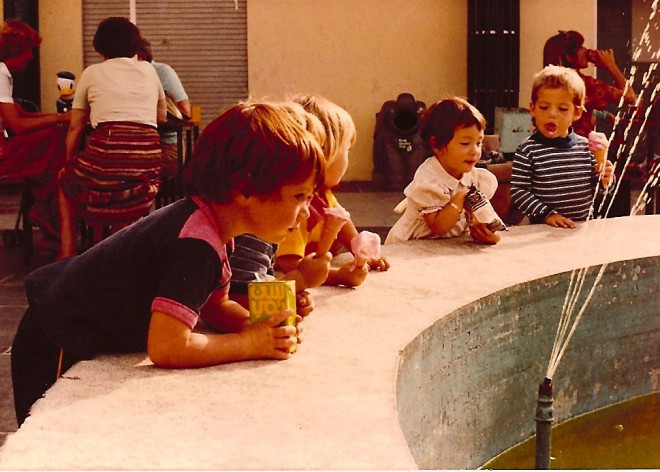

Anxious to get on land, we spent our first evening in the Medina, a direct lively contrast to the forsaken harbor. The Medina bustled, bartered, and whined traditional strains of Arab music; it begged as handicapped and mutilated men, women, and children languished throughout the streets with outstretched hands; it harked wares on street corners; it was a labyrinth of stalls grouped by trades of tailors, weavers, fruit and vegetable vendors; and it was a curious parade of veiled women with trays of flat bread dough on their heads scurrying to sunken, curb-level stone peephole entrances in the streets. Thoroughly intrigued, we stooped to peep in and beheld underground centuries-old, wood-fired ovens—community ovens of sorts—that baked individual households’ daily bread. Obviously westerners, we stood out as coarse threads within this finely woven tapestry. We elicited many a stare, especially with Brendan bouncing in his backpack. Sean was a magnet—dare I say “chic magnet”?—as women were drawn to his deep, auburn-red hair, reaching out to touch. One woman approached us and cradled Brendan’s bare feet in her hands, worried that he would catch cold. For us, this October Indian summer evening was warm. She thought otherwise.

As we meandered in the lively confusion, the stares melted into smiles, hellos, oft-spoken French, and invitations to taste their tangerines, breads, or just talk. Brendan couldn’t get enough of all the sights. He stood erect in his pack practically the whole time, wide-eyed, taking it all in. Sean was a trooper, as we walked a lot and he carried on. Being only three, however, he suddenly had the urge to pee, and there, standing before a stall and a peephole bakery, we were at a loss! Before we had time to figure something out, an attending gentleman whisked Sean away inside upstairs, returning with him in just minutes. Intrigued that Sean was able to enter a private living quarters, we peppered him with our curiosity as to what it was like. Relieving himself, it seems, was no big deal, he just aimed for “a hole in the ground.”

We only stayed briefly in Casablanca, having unfortunately boxed ourselves into a tight timeline to be in Dakar by Christmas, where we had scheduled to meet some friends from France. Although it was only the end of October at this point, we still had much sea to cover with stops still intended in Agadir, Morocco, and the Canary Islands, before arriving in Senegal. Nevertheless, these few days in Casablanca were “kid time” and we relaxed around some city parks, a cafe or two, and a little children’s-sized train ride for Sean before sailing on to Agadir.

The sail down the coast was a welcomed and calm easy downwind leg, yet striking and remarkable as we were awed by sand dunes of the Sahara Desert spilling to the edge of the sea. This was the extreme western edge of the Saharan Desert, and it was incredible to just see it—just there. I kept expecting Lawrence of Arabia to come flowing down a crease in the dunes on his majestic mount. But even out at sea we couldn’t escape the effects of this expansive natural phenomenon. Well before we could even see the coast, the sails began to take on an orange hue as red sandy dust accumulated in the folds of our sails and canvas covers. The sun was sometimes even veiled by an orange-red pall cast by the desert dust-laden horizon.

Nestled at the foot of the Atlas Mountains, Agadir of today is a completely new city, rebuilt after the original one was mostly flattened by a catastrophic earthquake in 1960. It has become somewhat of a European winter tourist destination, but in 1982 there were only hints and faint beginnings of these changes to come. There was no pleasure craft marina then, so we sailed into the dirty fishing harbor that reeked of rotten fish, thanks to a sardine processing facility situated right on the wharf. This rendered the water one mass of smelly goo as the waste was most obviously just dumped into the harbor. Cowabunga was rather pitiful, instantly incased in this gunk, as the hull became outlined with a yellow greasy film that bobbed up and down along the waterline. There was a constant underlying odor of stagnant sardines everywhere, something akin to the smell from oil lingering in the kitchen from a deep fried meal the night before—only much worse. I would cover my nose so I could fall asleep at night.

Belying this initial repelling impression, however, was the extreme generosity, courtesy, and genuine friendliness of the locals, so similar to our experience in the Casablanca Medina. They wanted to tell us about their city, their culture, their religion, their customs, their language. The post office attendant bid Michel share tea with him (not an easy feat for Michel since he really dislikes tea!) while he waited for a phone line to become available. Someone in the harbor lent Michel a scooter to go pick up a load of tangerines. A shoe cobbler in the open-air market could repair Michel’s broken flip-flop—for a pittance.

Michel was taken off guard by all this since he had initially harbored some hesitations, albeit even some prejudices toward these people—he admitted—given France’s long, and tumultuous colonial history with Arab North Africa, in particular, the bitter war with Algeria that permeated French life and current affairs during his childhood. Michel's father even served with the French army in France’s war with Algeria. We were won over by these gentle, sincere people. Morocco seduced us.

We also learned that bartering for goods and services was all part and parcel of daily life. When Michel returned to the market the following day to retrieve his repaired flip-flop (which in itself was surprising; after initially seeking to buy a new pair—with none to be found—this was the only solution), he quickly understood that just paying the initial asked-for price of just a few cents was unacceptable. A pantomime of price negotiating of sorts ensued, whereupon Michel performed as was expected of him, saving his honor, and the cobbler’s, as he he declared the few cents less an acceptable compromise.

With our load of tangerines (and NO sardines, having been sufficiently disgusted on that point), we headed out for the Canary Islands, and—unintentionally—our first major storm since leaving France two months earlier (with an average wind speed of 50 knots—nothing to sneeze at). Although the wind was violent, the sea wasn’t. It was, however, huge. Sean was a bit seasick at first, but not scared. Brendan was more annoyed that he kept getting knocked down, and at 8 months old, he was just sort of getting his “sea legs” so to speak. The next morning after the storm abated, I couldn’t get over the incredible height and volume of the swells. I popped my head outside the companionway to gauge the situation and saw a cargo ship nearby. The impressive swell towered above us, with the cargo teetering on the top of the rolling wave, and then it slid way down into a vast valley below us and we, instead, shifted up to the top. It seemed like a slow motion roller coaster, something as I imagine the movement of swimming pool water might be during an earthquake, except this was “cartoonesque” proportions. Having been somewhat blown off course for 24 hours, we were able to verify our position through VHF radio contact with the cargo, and got back on track to the Canary Islands.

Again, since we were somewhat in a hurry, we knew we couldn’t do the Canary Islands justice, so we concentrated on just one island, the volcanic Lanzarote, a true surprise. Austere, yet captivating in its black volcanic desert beauty, there were miles of landscapes of black sand, hardened lava fields, and spectacular vistas. There were even camel caravans for tourist promenades. Curious small vineyards, cultivated with individual plants nestled in protective rocky semi-circles, popped up here and there.

A quick puddle jump to Las Palmas on the nearby island of Gran Canaria, for just a brief day or two in order to fill up on provisions and onward we trekked for the week-to-10-day sail to Dakar.

It was still early in our adventure and every new landfall and sea journey was still a discovery for all of us. Michel and I were still learning things about the boat, navigating as a team, determining a good system for our watches, dealing with stress, varied weather conditions, and anchoring tactics. Sean and Brendan were growing, changing, learning. Brendan was quickly rolling through his baby stages: new teeth, beginning to crawl, exploring more in, and around, the boat—prompting us to try and stay one step ahead of him for installing safety measures. He was beginning to assert himself: determination, long memory, impatience...whereas Sean was becoming a social chatterbox and a promising fisherman. At 3 years old, he had just recently caught his first fish, and was duly proud.

Disappointed that our explorations of Morocco and the Canary Islands were so brief, it was nevertheless a valuable lesson well impressed upon us: Don’t make plans for specific dates too far in advance. It was the end of November now, and our timeline to be in Dakar to meet friends had restricted us too much. Too many unknowns can, and do, come into play when sailing, and we needed to learn to give a wider berth to those eventualities. Indeed, we had no sooner left Las Palmas, still motoring out of the harbor channel, setting our sails, when the engine just quit—permanently. We had no time to go back and deal with the problem. We just set the course for Dakar and would deal with it there.