Part Two...And Other Lessons We Learned

/Engines: Always the Epitome of Equipment Failure

From day one, when we first began our adventure with Cowabunga in France, and while we were still "feeling our oats" learning to sail and become comfortable with a water-borne lifestyle, our engine was an ongoing source of anxiety with break downs on a regular basis. Several years later it finally did give up the ghost and we had to give in and buy a new engine. In the interim, however, many a planned and unplanned stop from Portugal to Dakar, to Salvador da Bahia in Brazil, and finally Florida, were fraught with woes, worry, and anxiety due to engine repairs, diagnosing the problem or problems, finding someone who could find the problem, worries for the cost, searching for parts, waiting on ordered parts, or even trying to manufacture parts. Many of these engine-related experiences turned into epic moments, nevertheless sometimes fostering fond memories and friends for life, despite the circumstances. Such was the case in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, and the family of Jakaranda, with whom our lives still cross paths today.

We arrived in Salvador, or Bahia as it is most commonly known, well north of Rio de Janeiro, almost a year-and-a-half after we had first arrived in Brazil. We didn't intend to stay here long. Just a quick "look-see," get the lay of the land, a few walkabouts with the kids, catch up on our mail from General Delivery at the American consulate, some routine engine maintenance: oil and filter changes and what-not, and then continue on up the coast. So, one afternoon, after having accomplished the routine engine maintenance work, Michel went to start it up, and nothing. He tried and tried, still nothing. It didn't make sense since we had just used it several days earlier for anchoring in this harbor. During the next few days, Michel went down the diagnostic list of what he could and should do trying to discern what the problem could be. Nothing was working. He began to reach out to some of the other boats in the anchorage. One person would know about this, and someone else knew about that. Someone had a certain tool, and someone else had another. Another fellow cruiser had the same engine, and knew it backwards and forwards, he said. Slowly, our engine problem became the whole anchorage's problem. For almost three weeks, our engine was the focal point of the afternoon activity. After everyone had tended to school work, grocery shopping, and lunch, a sizable contingent of "do-it-yourselfers" amassed onboard Cowabunga with their favorite wrenches, screwdrivers, and what-not, for the latest round of diagnostic session of the Cowabunga "repair-a-thon."

Since the engine was centrally located inside Cowabunga, the whole interior was put asunder while the engine was slowly dismantled—different parts everyday. It was extremely difficult for us to do anything other than sleep there. So the kids and I became rather itinerant in that families from other boats took us onboard, fed us, or would take the kids during the day. The evenings we were wined and dined from one boat to another, and many an impromptu party erupted. We all organized occasional outside tours in town, and a couple of the older teenage girls became faithful, wonderful babysitters.

The Franco-Swiss family of Alec, Nadette and their two children aboard Jakaranda were lifesavers. Jakaranda was a very big, custom-built, comfortable sailboat. We could fully stand up inside with plenty of individual space. It was almost cavernous, and for a cruising monohull, that was pretty amazing! Since it was painted a signature violet/pink hue after its namesake flower, Jakaranda was quite a visible landmark in the anchorage.

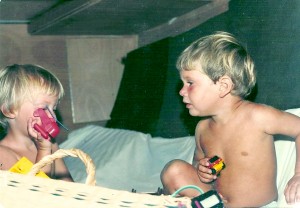

Alec also had a dedicated, spacious well-equipped workshop space onboard. A lot of our engine ended up there in various stages of analytic decomposition. Also, since we couldn't charge our batteries as our engine was in complete disarray, Jakaranda would lift their anchor and tie up alongside Cowabunga on occasion and run their engine to charge our batteries. Our four children, all close in age, became fast friends. Both Brendan and their little girl, Gougou, were only about a year apart—barely 2 and 3 years old—and of similar temperamental characters. They got along very well and with the two boats tied up side-by-side, it proved to be a magical solution, keeping both little tykes occupied and happy in each other's company. Consequently peace reigned across the two decks and we parents were soothed. Jim and Sean at 8 and 4 years old kept each other company with Lego, swimming, and playing with the other kids in the anchorage.

With all this communal help, the engine was eventually put back into working order. It seems that multiple factors conspired to the bring about the engine's downfall, and it took a village to get us back on our feet. We were overwhelmed by everyone's generosity and decided to host a thank-you party. After tallying up the number of people who helped us out, we realized that Cowabunga was too small to host a party for over 20 people. Again Jakaranda came to our aid and rafted up alongside us. With two deck widths to spread out over, we had a party to remember.

Other Missteps

I can't overemphasize how important it is to be patient when sailing. By nature of the type of propulsion—powered by the wind—one can't help but incorporate patience into the daily diet. Nevertheless, there were always other reminders that would surface from time-to-time. Along with our dragging anchor incident in the Antilles that ill-served Michel since he broke his fingers, (see "Off Goes the Wedding Ring," Vignette post July 19, 2011), the gods of the seas had decided that we were still too anxious and rushed on occasion. Or maybe it was more that we just didn't take a hint. Sometimes we needed to be hit over the head.

Actually one of the earliest very close mishaps we survived occurred well before we left France, almost two years prior to our transatlantic journey. We had been sailing for a short vacation up the coast of Brittany and Michel needed to get back to his office for work. Calendar time waits for no one, but weather conditions don't always cooperate. Sean, our only child at the time, was only 1, and he was with us. Sailing back down to Bordeaux, the wind and seas were a bit agitated, but nothing tempestuous. We targeted the quaint harbor of St. Gilles Croix de Vie for an overnight stop, and were looking forward to this snug, protected harbor and a calm meal. By the time we arrived in front of the narrow harbor entrance, the tide was going out, and there was quite a bit of swell from fairly rough seas. We had never been here before, and thus we didn't know the harbor. We were used to this, however, and in such cases we would thoroughly scour the charts and nautical instructions that gave every bit of pertinent information one would ever need to know to enter a port blindfolded. For St. Gilles Croix de Vie, there was an exceptional warning: "DO NOT ENTER THE HARBOR WHEN AN OUTGOING TIDE COINCIDES WITH A LARGE SWELL." The narrow entrance was bordered by two long cement jetties and various barely submerged rocks. The "outgoing tide–large swell" phenomenon literally created surf-worthy waves that rolled into the harbor at the jetty entrance. A boat caught in such conditions could find itself nose-diving end-over-end, a perfect "crash and burn" scenario: knockdown, sinking, and thrown to the rocks.

These detailed books of nautical instructions exist for a reason, especially with such specific stern warnings. However, from our viewpoint on the water just outside the entrance, conditions certainly didn't look that menacing and the calm channel just beyond the jetties was so enticing this late in the afternoon. Compass direction straight for the entrance. Just as we were beginning to pat ourselves on the back as our bow began to cross the limit at the jetty, ("what's the big deal," "piece of cake..."), a good surfing wave caught our stern, threw Cowabunga completely sideways, knocked down, and we were headed straight for the rocks and cement wall. Michel had no control over the wheel as the rudder and engine propeller were completely out of the water. Sean, down below, was thrown about. We had panic on our faces and for several seconds pictured the demise of the boat here and now! Then something let up, Cowabunga regained its upright position, and the wave literally spit us out in to the calm channel just feet away. Breathless and thankful, we vowed then and there to never take nautical instructions lightly, and never to be in hurry, no matter what the calendar date.

Several years later in Brazil, we proved to ourselves that we had learned this lesson, when a silly argument between Michel and me forced us to bow to the more powerful rule of the sea. We were sailing north after leaving Bahia, with an ultimate destination of Fortaleza in very northern Brazil. It would be our last stop before Cayenne, French Guiana. We had been at sea several days, and the conditions were pleasant. Arriving near St. Joao de Pessoa, we studied the charts and it looked fairly inviting. We thought it might make for a nice, one- or two-night unscheduled stop, a few nights' good, uninterrupted sleep, and a chance for the kids to stretch their legs a bit on land. Nevertheless, the chart did show a lot of reefs, shallow areas, and underwater rocks. It was high tide, and Michel was pretty confident we could take a short cut, avoiding the longer, winding marked channel. I preferred, however, that we follow a cargo just ahead of us that was entering via the channel. Michel kept insisting we could take the short cut over the reefs. We began to argue rather vehemently about it, when the wind just grabbed the chart in question from the cockpit table, and whisked it away. We were both cut short, our mouths agape. Our decision was made for us. There was no choice but to head back out to sea, direction Fortaleza. Amid our deep disappointment and unbelievable surprise, we were wise enough to know not to tempt danger without our only valid tool in our hands. Forefront in our minds was the lesson of St. Gilles Croix de Vie: Don't discount explicitly forewarned dangers.