Christmas in Dakar

/Santa swapped out his sleigh and reindeer for a French military helicopter, landing on the soccer field at the French military base on the outskirts of Dakar. Our 3 year-old son, Sean, was ecstatic. Christmas in this western outpost of Africa was indeed something out of the ordinary for us.

Following our arrival in Dakar, Senegal, about a month earlier, and the successful heroic efforts on the part of the crew of the U.S.S. O’Bannon (see Vignette U.S. Navy to the Rescue, posted July 2011) to right our wronged engine, we had moved on and acquainted ourselves a bit with dusty Dakar—somewhat of a bustling frontier crossroads for an eclectic cast of characters. From our acquaintance with the U.S. Embassy Vice Consul to itinerant French and American students, hitchhiking foreigners just passing through, visiting professors from the U.S., a Basque fisherman, assorted Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) volunteers, and members of CARE and the Peace Corps, we met them on the fly, in the marketplace, on the beach, at the post office, at bus stops. They spoke English, French, and Oulof—the local dialect.

It was hot, dusty in the city, yet we were cozy tucked away in the lagoon of our tropical anchorage at the resort island of N’Gor. The island of Gorée, infamous for its slave trading operations in the 1700s, lay not far off the coast. And although somewhat of a misplaced tropical haven on the outskirts of the gritty city, the island of N’Gor was nevertheless a welcome respite for us. It was easy living for our boys, after the recent tense situation in the industrial harbor. And for much the same reasons, there were several other sailboats that sought refuge at N’Gor so as to temper the city experience of Dakar proper.

Indeed, our contact with local Senegalese citizens was somewhat unfortunate and edgy—an experience we shared with other white tourists. It was not as pleasant as we hoped it would be. As in many former European African colonies, Senegal, too, bears the scars of the former colonial white-dominated social order and government. Cultural divisions were still quite apparent as borne out by then current race and class status. The Senegalese population and the white French expats distrusted each other, and although their relationships intertwined daily via jobs, schools, and at the marketplace, young white mothers still enjoyed a class luxury of having a black housekeeper and a children’s nanny or “nounou,” whom only too often received paltry wages.

Consequently, the local Senegalese “man on the street,” was generally quite reserved in dispensing any goodwill toward white men. There was always a detectable undercurrent of hostility. A white person was seen as a wallet, a source of cash—preferably dollars. Buy this, buy that, give me this, give me that…In our experiences with street peddlers in other countries up to that point in our travels, a simple “no” would suffice. In the streets of Dakar, “no” left us wide open to an avalanche of rude retorts and enraged “in-your-face” confrontations, all thrown at us while we attempted to mind our own business, continuing on down the street. Our first taste of this, and hint of what was to come, was shortly after our arrival, tying up alongside the industrial harbor wharf next to the U.S.S. O’Bannon. We were harangued and solicited all day, every day, and into the night. It was hard to sit outside on the deck as passersby relentlessly harked their wares, or sought handouts. It was hard to stay down below since it was so unbearably hot and humid. It was hard to eat while they so obviously wanted food and whatever else caught their eye. They brazenly jumped on our deck and tried to steal items right in front of us. The U.S.S. O’Bannon crew quickly mounted the guard with a 24-hour watchman, allowing us some peace of mind to be able to sleep somewhat at ease.

Given this underlying hostile atmosphere, the island of N’Gor evolved into a refuge for white tourists: a small tropical island, with a big chain resort hotel, the requisite palm-thatched palapa umbrellas, drinks served on the beach, and its very own intimate aqua-blue lagoon—not necessarily in line with our taste for a “vacation” locale, but a compromise taking into account our needs at the time. Some of the white Dakar residents would spend a few days on N'Gor at their weekend bungalows. Thus, one weekend we met the U.S. Embassy Vice Consul and her husband; we were promptly invited to a barbecue at their nearby beach bungalow, along with a colorful guest list of foreign characters, all passing through at the time.

It was the Christmas holiday season, and before leaving France that past August, we made the mistake of arranging to meet Michel’s then-business partner, Christian, for Christmas in Dakar. Since Christian’s brother was in the army in Dakar, it seemed like a good opportunity for a fun get-together and a final farewell to Christian before our definitive break from this part of the world, since we would be crossing the Atlantic to Brazil some time in January. By the same token we could all experience Christmas together in an “exotic” location. However, we quickly realized it had been a mistake boxing ourselves into such a fixed deadline. It left us no time to visit the Canary Islands, or spend as much time as we would have liked in Morocco. Not only that, we began to realize that there could be too many other unknowns to upset plans, like fickle or sudden weather changes, and unforeseen equipment breakdowns. Such events can always drastically alter a timeline. We hurried to Dakar, and with our major engine breakdown just as we were leaving the Canary Islands, it made for a hectic time, all with having to prepare for our Atlantic crossing.

For the kids, though, it was important to make time for Christmas, and so we did. We were invited to a traditional French Christmas Eve feast at Christian’s brother’s home on the military base, complete with a busy day of varied activities for a crowd of children, including a Disney video (a real treat for Sean since we had no television on board and he had never been to a movie theater), highlighted by Santa Claus’ landing in a helicopter. We “made merry” and then quickly got back to the task of preparing our passage to Brazil shortly thereafter.

Never having crossed an ocean, this was a huge project for us and it was daunting. We needed to foresee every possible scenario, good and bad. We estimated that it should take about 30 days, from Dakar to Rio de Janeiro: at best maybe a few days less, at worst—in the case of major breakage—well, we preferred not to mull over a possible "castaway" scenario. We simply had to have more than enough food. We couldn’t depend on fishing to provide enough food; that was always an “iffy” option. So, along with the usual minor hardware repairs, sail repairs, boat upgrades, painting, canning and drying foodstuffs, umpteen shopping trips, and making lists upon lists of “to-do’s,” we planned on beaching Cowabunga at some point for the annual hull cleaning. At best, counting on a 30-day crossing, we couldn't afford to be slowed by barnacles and other sea creatures that were already beginning to hitchhike along for the ride in the past few recent weeks.

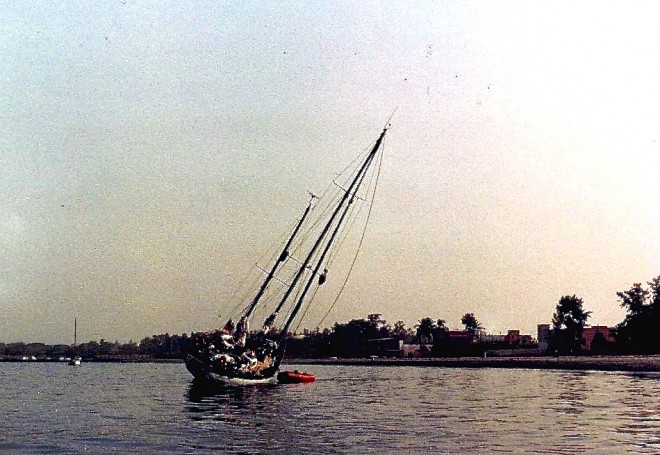

There were no facilities in order to haul out a sailboat in Dakar, so by calculating the highest and lowest tides of the month, Michel honed in on the days and a beach in a nearby bay that would be the best option. Voluntarily beaching a 42 ft. sailboat is not an easy undertaking, and rather nerve-wracking at best. Prior to beaching it, everything inside the boat has to be put in its proper place, well tied down, with additional forethought given to what object or objects could crash or spill at a 70°-80° angle for an entire day, as the boat lay practically horizontal on its side. So on the designated day, we were ready as the clock struck high tide. We positioned Cowabunga parallel to the beach, at the highest point possible on the shore, with the keel barely touching the sand in the high water. Slowly the boat would begin to lean towards a resting place on the beach as the water pulled out from under it. Like a beached whale, Cowabunga was an awkward hulk posed on its starboard side the first day, only to turn its cheek for the second round on port side the following day.

It’s a full hectic day to scrape, fit in in some quick hull repairs, and a coat of anti-fouling paint all before the tide comes back in. And then there is always an anxious moment just before full flotation at high tide. One is never quite sure that this beached whale will be completely, fully righted. Since Brendan was only 10 months old, and still adhered to a full infant schedule of regular meal times and naps, I couldn’t be of much help in the labor department for hull cleaning duties. An extremely generous couple on a neighbor boat provided “base station” access for me and the boys for the two days, along with being dedicated laborers for Michel.

So, attempting to remain true to our principle of sticking to certain deadlines as much as possible, we targeted late January to head out across the Atlantic Ocean. Although Dakar turned out to be somewhat disappointing, and not at all what we had expected in this part of Africa, Morocco balanced things out being so much more pleasant and surprising than we expected. Nevertheless, there were some unique moments and memorable encounters during our Dakar experience. Michel’s own foray into the main marketplace one day led him to a curious group of tall, black-robed hooded Moors from neighboring Mauritania, huddled around a fierce fire where they were creating silver jewelry. Michel, who (as an architect) has a rather keen sense of unique artistry, spied some sleek handmade silver bracelets and thought they might make dramatic hooped earrings for me. And so these artisans mulled over the challenge, and were able to transform the bracelets into earrings right then and there over their fire. Michel surprised me with them for Christmas, and I still wear them today—a tangible piece of memory from our past, and one of our better souvenirs of Dakar.