Coming to America

/"Bam!" Oh %#@!! Here we go again. Déjà vu. The headstay on the roller furl broke and it all came crashing down—again, the third time in three years. A year earlier we were off the coast of Brazil, under a light wind, when a part gave way on the bottom furling drum that was anchored by the turnbuckle on the deck. This time it turned out to be a stainless steel plate at the top of the mast. Again, the whole genoa and heavy tubes crashed into the water. The extra wrinkle this time, though, was that Michel was doubly handicapped: first with his hernia, and then in the panic of trying to lower the sail as it was wildly flailing about, his arm got severely whacked by the winch handle on the mast. At first we weren't sure if his arm was broken or not since he was in a lot of pain and couldn't do much. Initially I had to go it alone. This all happened at 8:00 a.m. and by 4:00 p.m. we had finally inched the last bit of sail and tube onto the deck by hand. The heap, now on our deck, weighed tons, especially because the sail was thoroughly soaked. Final damage assessment: ripped sail, a few bent tubes, broken headpiece attachment for the mast. We knew the scenario: jury-rig the forestay, get into port, see about repairs. So hailed our arrival in Fort de France, Martinique.

Martinique was another kind of France, very different from the French Guiana version we had left a week earlier. Whereas French Guiana was dominated by its penal history, the Amazon jungle, and jousting current-day forces that tried to maintain or upset a balance of the indigenous tribal heritages, Martinique was France "en vacances"! Along with its sister islands Guadeloupe, St. Barth, St. Martin, and other smaller Caribbean French tropical enclaves, Martinique was a winter playground for motherland France, for those who came from the "metropole" to escape the winter doldrums.

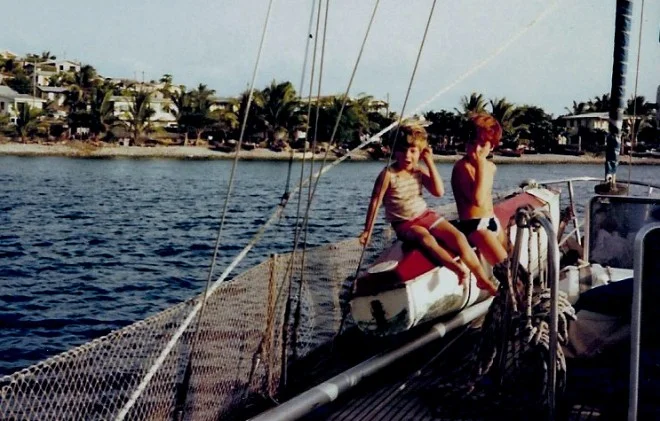

Indeed there was a different vibe here. Yachties weren't here to work. They were touring the Caribbean, enjoying anchorages, beaches, the sun. And the yachty population was very international. We began to run into some American cruisers and most notably also a few families. It was one of the first times that Sean and Brendan interacted in English with fellow kids on a boat. Although Martinique was definitely "touristy," the local population was pleasant and helpful. We got our repairs underway and consulted a doctor for Michel's hernia. Due to a prescribed downtime of at least two months following such an operation, it wasn't going to be feasible for us to take care of the problem here. The summer hurricane season was imminent and we weren't keen on being at anchor should such weather come up while Michel was in a compromised physical condition, convalescing. So on to plan B: a more direct route to Florida and a longer stay there than originally planned.

This is when we were thankful that we had the foresight to begin the process for Michel's residency "green card" application for the States before we left France. The file was on hold at the U.S. Consulate in Bordeaux, ready to be sent to another U.S. consulate wherever we happened to be, upon a simple request. It was a simpler process in those days of the 1980s, and within a week, the diplomatic services had transferred Michel's file to the U.S. consulate in Fort de France. A few interviews, more paperwork, and voilà, he was granted a green card in short order. A preliminary visa was stamped into his passport with instructions that his final residency card would be issued to him upon our clearing immigration in Port Canaveral, Florida.

Thanks to some "friends-of-friends" and former office colleagues of Michel's in Cayenne, we were wined and dined and invited along to see some of the sights of Martinique before we lifted anchor to continue our journey north. We made one last stop in Martinique in the picturesque town of St. Pierre that been devastated by a catastrophic volcanic eruption of Mt. Pelée in 1902. Entire fleets anchored in the harbor at the time also sank, many of which were still underwater.

Michel was becoming more and more uncomfortable due to his hernia, so we decided that we needed to amble up to Florida sooner than later, targeting lesser towns and anchorages so we could slip under the radar of customs and immigrations officials to avoid the tedious officialdom for each island for just one-night stays. Then what began as a pleasant evening anchorage at the island of Dominica, quickly turned into a nightmare (see vignette Off Goes the Wedding Ring, posted July 19, 2011) as our anchor dragged, and a series of mishaps rendered Michel wounded with a bloodied swollen hand and broken finger, and a sudden unscripted all-night sail to the small islands of Les Saintes. A doctor in Les Saintes the next morning patched him up, but now Michel was really hobbling along. Nonetheless, we were able to continue making single night stops up through Guadeloupe, Montserrat, St. Kitts, St. Barthelemy (aka "St. Barth"), and finally the dual French/Dutch island of St. Martin (where we discovered from the young couple anchored nearby that the vessel they captained belonged to Bob Dylan; he wasn't on board).

After a quick month and-a-half of scooting up the islands, we bid goodbye to these tropics, and sailed out of St. Martin for Port Canaveral, across the Bermuda Triangle. I was apprehensive. Not for the Bermuda Triangle, but for our sailing under less-than-ideal conditions since the roller furl and forestay held thanks to a makeshift repair (not being able to find or make thoroughly satisfactory parts in Martinique), and Michel was physically compromised with his hernia and now broken finger. I wasn’t reassured should we encounter some bad weather. As it was, we only had a few annoying days of beating into some light headwinds—not too nasty.

Not far off the coast of South Florida, we passed a sailboat, and contacted them by VHF radio, much like we usually did with cargoes. They were headed to the Virgin Islands, having left Melbourne, Florida, near Port Canaveral, they said. We exchanged weather forecast info, and obtained some local information about this upcoming landfall port, since they knew it well. Then, quite reminiscent of our blind date meeting with the cargo captain in Buenos Aires, we were having dinner two years later on Cowabunga with John, a young man we had hired to do some carpentry work onboard, when we all discovered that we had already met on the high seas off the coast of South Florida two years prior. John was on that sailboat headed to the Virgin Islands! Now he lived just a mile or so down the road from our anchorage in the Banana River in the Intracoastal Waterway near Melbourne.

Deep in the night of June 22, 1985, we spotted the blinking beams of the Port Canaveral lighthouse. Sunrise the next morning revealed a seemingly virgin coastline graced with white sand and low-lying foliage. Then the sudden incongruent images of launch pads jarred the skyline accompanied by the hulking Vehicle Assembly Building of the Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral. After three years, the west coasts of Spain and Portugal, Africa, the length of South America, and the West Indies, we had come to America.